Abstract

LITERATURA AKADÉMIKA, (LIBERDADETL.com)— This paper explores the cultural significance and socio-economic dynamics surrounding the seasonal emergence of the sea worm (Palola viridis), locally known as Meci, within the Fataluku community of Lautem Municipality, East Timor. Traditionally revered as both a delicacy and a symbol of ancestral connection, Meci plays a central role in cultural rituals, oral traditions, and communal identity. However, environmental changes, economic pressures, and modernization are increasingly threatening traditional knowledge systems and disrupting the sustainable harvesting practices that have governed Meci collection for generations.

Objectives of the study include documenting local knowledge related to Meci, analysing socio-economic changes affecting its use, and identifying sustainable practices rooted in community traditions.

Methodology involved qualitative fieldwork, including in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with elders, youth, and fishers in the Fataluku community.

Key findings reveal significant shifts in harvesting patterns, diminished participation of younger generations in traditional practices, and increased commercialization. Despite these challenges, community-driven strategies are emerging to preserve cultural values and promote sustainable marine resource management.

By examining Meci through cultural and ecological lenses, this study highlights the importance of integrating indigenous knowledge into national conservation and development frameworks to support both biodiversity protection and cultural continuity.

Keywords: (Palola viridis), Meci, Fataluku, East Timor, Socio-Economic Change, Local Knowledge, Sustainability.

I. BACKGROUND

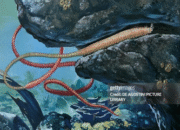

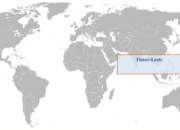

The sea worm (Palola viridis), commonly known as the Palolo worm, is a fascinating marine species found primarily in the tropical regions of the Indo-Pacific. Its distribution includes countries such as Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu, Indonesia, the Philippines, Tonga, Papua New Guinea, and Timor-Leste. These worms inhabit coral reefs and rocky coastal areas, where they remain hidden in burrows or beneath rocks during the day (Schulze, 2006).

In Timor-Leste, Palola viridis, locally known as Meci in the Fataluku language, is a species of marine polychaete worm that appears seasonally in the coastal waters, particularly along the shores of Lautem Municipality. Its emergence is closely synchronized with lunar cycles, typically occurring once or twice a year, and is met with anticipation by local communities. Ecologically, Meci contributes to the marine food web and is regarded as an indicator of healthy reef ecosystems. For the Fataluku people, its arrival is more than a biological event, it is seen as a natural gift from the sea, intimately connected to environmental rhythms, seasonal changes, and community traditions.

Within the Fataluku community, Meci holds deep cultural and symbolic value. Beyond being a seasonal delicacy, its harvesting is deeply woven into traditional knowledge systems, ancestral cosmologies, and communal rituals. The collection and sharing of Meci are not merely subsistence or commercial activities, they are acts of cultural expression that mark seasonal transitions, strengthen kinship ties, and reinforce the community’s spiritual relationship with the ocean (Maleki Ratu, 2025)

Elders play a vital role in transmitting knowledge about the timing, harvesting techniques, and cultural meanings associated with Meci, while younger generations participate through observation and practice. This intergenerational exchange ensures the continuity of identity, oral history, and environmental stewardship, maintaining a profound connection between people and their marine environment.

The sea worm (Palola viridis), locally known as Meci in the Fataluku language, is a seasonal marine species that holds ecological, cultural, and spiritual significance for coastal communities in Lautem Municipality. Found along the eastern coast, Meci emerges annually in the waters near Tutuala, Com, and Lore villages, where its appearance is eagerly anticipated and deeply respected.

The harvesting of Meci in Tutuala and Com typically occurs twice a year, around March and April, coinciding with specific lunar cycles. In these villages, the Maleki clan is recognized as the first to have discovered Meci. As a result, they are culturally acknowledged as the traditional custodians or “owners” of the species in this region, a role that carries both respect and responsibility and In Lore 1 village, Meci appears once a year, usually in March. Here, the Chaylor-Ziataana clan is credited with its discovery, and likewise holds a special cultural status connected to the worm.

These local traditions reflect a rich system of indigenous knowledge and ecological awareness, where the emergence of Meci is not just a biological event but a moment that marks seasonal change, reinforces social structure, and strengthens spiritual ties to the sea. The knowledge of timing, harvesting practices, and ceremonial roles is passed down through generations, ensuring the preservation of both biodiversity and cultural identity.

I. LOCAL MYTHOLOGIES AND ORAL HISTORIES IN THREE VILLAGES IN LAUTEM MUNICIPALITY.

1. Fieldwork

2. Map of East Timor

3. Mythological Origins Of Meci In Com And Tutuala Villages

In Com and Tutuala villages, a coastal community in the Lautém Municipality of eastern Timor-Leste, the seasonal appearance of (Palola viridis) locally known as Meci is not only a natural phenomenon but also a deeply rooted cultural and spiritual tradition. According to local mythology, the discovery of Meci is attributed to a revered ancestral figure, Maleky Ratu, a respected elder of the Fataluku ethnic group.

The myth recounts that Maleky Ratu first observed the appearance of sea worms at a coastal site known as Kusar Helapuna. Attuned to the rhythms of the sea and moon, he noticed their emergence in synchrony with specific lunar cycles. Recognizing their abundance and nutritional value, he shared his knowledge with the community.

Importantly, he taught the people how to harvest Meci in ways that respected the natural cycles of the ocean. This marked the beginning of a tradition that would become integral to the cultural and ecological identity of the Fataluku people.

In this narrative, Meci is considered not merely a food source but a sacred gift from the sea, bestowed by nature and ancestors. The annual harvest serves as a symbol of harmony between humans and the marine environment, reinforcing the community’s spiritual connection with the ocean and its cycles. This mythology plays a vital role in shaping the worldview and environmental ethics of the Fataluku, promoting respect, gratitude, and collective responsibility toward marine resources. The Meci harvest is a highly anticipated seasonal event, particularly in coastal areas such as Com Beach, Walu Beach, and Loiquero Beach, and is celebrated in Lospalos, the capital of Lautém Municipality. The harvesting period is closely linked to lunar phases, with two primary seasons:

- Meci moko: The smaller preliminary harvest occurring in late March.

- Meci lafai: The major harvest, held in Abril, attracting large communal gatherings.

This harvest is more than an economic or subsistence activity, it is a cultural festival marked by communal labour, ritual observance, and celebration. Songs, dances, storytelling, and feasts accompany the event, transforming it into a moment of collective cultural expression and renewal. The shared experience reinforces intergenerational bonds, as elders teach the significance and methods of harvesting, while youth participate in cultural learning.

4. MYTHOLOGICAL DISCOVERY AND CULTURAL TRADITION IN LORE 1 VILLAGE

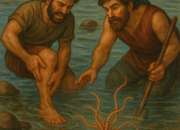

In the village of Lore 1, located within the Administrative Post of Lore in Lautém Municipality Timor-Leste, the sea worm Palola viridis, locally known as Meci, holds profound cultural and historical significance. According to oral tradition, the origin of Meci harvesting in this community is rooted in an ancestral myth involving two brothers Sairumalai and Mamanumalai from the Uma Lisan (Tribal House) named Chaylor Zia-taana.

As the story goes, during an episode of low tide, the two brothers ventured out to sea in search of fish. On the first day, they encountered nothing unusual.

However, on the second day, they discovered a strange, root-like organism emerging from the water. This unfamiliar creature, later identified as Meci, provoked their curiosity. While harvesting, one of them, Sairumalai, unexpectedly the right hand hit Sairumalai’s leg, causing a wound that bled a lot. after contact with the organism’s sharp end. Despite the incident, they collected a quantity of Meci and brought it back to shore.

According to the narrative, Sairumalai expressed concern about the safety of consuming this unknown creature, saying, “I will eat it first. If I die, tell our family it is not safe.” Upon tasting the Meci, however, he found the flavour unexpectedly pleasing. Encouraged by this experience, both brothers proceeded to cook and consume the Meci, preparing it using traditional methods such as saboko and budu, two local recipes still used today.

This initial discovery became a pivotal moment in the village’s cultural history. The brothers shared their find with their family and community, who then discussed how to integrate Meci into their subsistence practices. To ensure sustainable harvesting, the community employed a traditional method known as Attach the rope (Kesi Tali) a timekeeping and lunar-observation technique passed down through generations. This practice involved tying a string to mark the date of the first encounter and counting the days and lunar cycles until the next anticipated appearance. On the fourth day after the initial observation, a small-scale collection was undertaken. On the fifth day, a more substantial harvest confirmed the accuracy of their method.

Over time, this system became institutionalized within community practice, allowing the people of Lore 1 to synchronize Meci harvesting with lunar patterns. Thus, the event transformed from a moment of discovery into a ritualized seasonal tradition, deeply embedded in local ecological knowledge and cultural identity.

- The Meci harvest is a highly anticipated seasonal event, particularly in coastal areas such as Lore 1 Village is celebrated in Lospalos, the capital of Lautém Municipality. The harvesting period is closely linked to lunar phases, with one preliminary harvest occurring in late March.

Today, the Meci harvest remains a central cultural event in Lore 1, celebrated annually and symbolizing the community’s relationship with the sea. It is marked by collective participation, oral storytelling, ritual food preparation, and the reaffirmation of ancestral wisdom. The tradition not only sustains the community nutritionally but also preserves a key aspect of Fataluku intangible cultural heritage, illustrating the enduring interplay between myth, environment, and identity.

This study aims to explore the cultural, socio-economic, and environmental dimensions of Meci within the Fataluku community. Specifically, it seeks to document traditional practices and beliefs associated with Meci, examine how these have been affected by broader socio-economic and environmental changes, and identify pathways for sustainable use and cultural preservation.

2. CULTURAL CONTEXT OF MECI IN THE FATALUKU COMMUNITY

5.1. Traditional Beliefs, Rituals, And Taboos Related to Meci Harvesting

In the Fataluku worldview, Meci is not merely a marine organism, it is a sacred sign from nature and the ancestors. Its annual appearance is believed to be spiritually guided and must be approached with respect and ritual awareness. Traditional beliefs hold that the successful emergence of Meci depends on the harmony between humans and the natural world, particularly the sea.

1.Traditional Beliefs

In the cultural traditions of coastal communities in Lautem, the sea worm Meci is regarded as a sacred gift from the sea, bestowed by ancestral spirits. Its appearance during specific lunar cycles is not taken for granted, but received with humility and gratitude, as a sign of ancestral favor. The timing and abundance of Meci are seen as forms of spiritual communication—messages from the ancestors or nature itself. A poor harvest is often interpreted as a sign of disrespect or imbalance within the community or environment. The emergence of Meci is also closely linked to natural cycles, aligning with the moon and seasonal rhythms. This connection imbues Meci with symbolic meaning, representing renewal, fertility, and the deep interconnectedness between human life and the natural world.

2. Rituals

The harvesting of Meci is deeply rooted in ritual practices that reflect both spiritual reverence and ecological understanding. Before any harvesting begins, pre-harvest ceremonies are often conducted by elders or ritual leaders from sacred houses, known as uma lulik. These ceremonies involve offerings of betel nut, areca leaves, and other sacred items to local spirits, accompanied by invocations to ancestral beings for permission, protection, and blessings for a safe and abundant harvest.

A key ritual practice is the Kesi Tali timekeeping method an indigenous system using knotted strings to track days and lunar phases. This ancient method helps determine the precise moment when Meci will emerge from the sea. It is a sacred blend of cosmological insight and ecological observation, reflecting the deep interconnectedness of time, nature, and community.

When the time is right, the communal harvesting of Meci begins. Families and neighbors gather on the shore, often barefoot and moving with trditional song. This act is more than gathering food; it is a rite of respect for the ocean and the life it offers. The quiet, intentional nature of the harvest reinforces the belief that harmony with nature requires humility, discipline, and unity.

3. Taboos Related to Meci Harvesting

In the traditional communities of Lautem, Timor-Leste, harvesting Meci (Palola viridis) is a seasonal and communal activity deeply rooted in sacred practices governed by long-held taboos that ensure harmony between people, nature, and ancestral spirits. Disrespecting ancestral protocols by harvesting without ritual offerings or consulting elders is strictly forbidden, as Meci is viewed as a sacred gift, and neglecting these customs invites misfortune or a poor harvest. Greedy or wasteful collection is condemned since the sea provides Meci for sustenance and unity, not excess or profit, and such actions disrupt cultural ethics and spiritual balance. During the harvest, silence or respectful songs are observed to maintain spiritual focus, while loud talking, joking, or mocking is taboo because it offends sea spirits and breaks the sacredness of the moment. Harvesting outside specific lunar phases, determined through the ancestral Kesi Tali ritual, is prohibited as it ignores traditional ecological knowledge and ancestral guidance. Additionally, certain coastal zones and nearby forests are considered sacred (lulik) and can only be accessed with permission or ritual authority; trespassing violates spiritual boundaries and may provoke spiritual consequences. Collectively, these taboos embody profound respect for nature, spirituality, and social order, reflecting indigenous ecological understanding and a commitment to sustainable living, emphasizing that the Meci harvest is not merely economic but a vital cultural and spiritual tradition.

6. PREPARATION FOR MECI COLLECTION

6.1. Traditional Timekeeping

The Fataluku indigenous community holds a rich body of ecological knowledge about Meci (Palola viridis), cultivated through generations of intimate interaction with the marine environment. This knowledge enables them to accurately predict the seasonal emergence of Meci by observing natural cues such as lunar phases, tidal rhythms, and behavioral changes in seabirds. Passed down orally from elders to younger generations, this wisdom is transmitted through storytelling, communal discussions, and hands-on participation during harvesting activities. Such practices not only preserve cultural heritage but also reinforce sustainable resource management rooted in traditional science.

6.2. Family & Community Coordination

Family & Community Coordination plays a central role in the harvesting of Meci (Palola viridis) along the eastern coast of Timor-Leste. This seasonal event is not an individual activity but a collective effort involving entire families and village communities. Planning is done collaboratively, often led by elders who hold traditional ecological knowledge and understand the lunar timing of the Meci’s appearance. Each household contributes to the preparation, harvesting, and celebration, reflecting strong interdependence and shared responsibility. These practices not only ensure an organized and respectful harvest but also strengthen social cohesion, reinforce cultural values, and maintain a living connection between people, their ancestors, and the marine environment.

Family & Community Coordination plays a central role in the harvesting of Meci (Palola viridis) along the eastern coast of Timor-Leste. This seasonal event is not an individual activity but a collective effort involving entire families and village communities. Planning is done collaboratively, often led by elders who hold traditional ecological knowledge and understand the lunar timing of the Meci’s appearance. Each household contributes to the preparation, harvesting, and celebration, reflecting strong interdependence and shared responsibility. These practices not only ensure an organized and respectful harvest but also strengthen social cohesion, reinforce cultural values, and maintain a living connection between people, their ancestors, and the marine environment.

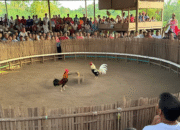

6.3. Traditional Cockfight Observation

Traditional Cockfight Observation is an important cultural expression in many communities of Timor-Leste, including those involved in Meci harvesting traditions. While often seen as a form of entertainment, cockfighting holds deeper social and symbolic meaning. These events are typically held during community gatherings or seasonal festivities, such as those marking the appearance of Meci. Observing cockfights offers a space for storytelling, social bonding, and the reinforcement of local customs. Elders often guide the younger generation not only in the rules and rituals of the practice but also in the values of respect, bravery, and tradition that it embodies. Though controversial in some contexts, within many communities it remains a key element of cultural heritage and communal identity.

6.4. Promoting Cultural Heritage And Identity

Promoting cultural heritage and identity is vital for preserving the traditions and values of local communities in Timor-Leste. Efforts should focus on encouraging intergenerational learning where elders pass down traditional knowledge, practices, and stories to younger generations fostering a sense of cultural pride and belonging. By strengthening the connection between tradition, the natural environment, and youth education, communities can ensure that cultural practices like Meci harvesting, traditional rituals, and ecological stewardship continue to thrive as living traditions, relevant to both present and future generations.

6.5. Tools for harvesting Meci

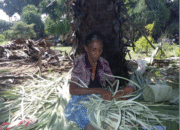

Prepare to Sew Square-Based Baskets Woven From Palm Fronds

Indigenous community members in Timor-Leste prepare to weave square-based baskets known locally as Bote, made from palm fronds. These traditional baskets are specifically crafted for collecting and carrying Meci during the seasonal harvest. Lightweight and environmentally friendly, Bote reflect not only the community’s deep connection to nature but also generations of craftsmanship, cultural knowledge, and sustainable practices. The act of weaving and using these baskets is both practical and symbolic—preserving ancestral skills while reinforcing identity, tradition, and ecological respect.

- Traditional Light that made from the Dried Coconut Leaves

Indigenous communities apply traditional ecological knowledge to enhance the Meci (Palola viridis) collection process, including the strategic use of dried coconut leaves (kaliuk) to produce light and heat during harvesting. These dried leaves are ignited along the shoreline or in shallow waters where Meci are expected to emerge. The firelight serves a dual purpose: it illuminates the area during night-time of harvesting, and the heat generated is believed to stimulate the Meci to rise from the seabed. This method reflects a deep ecological understanding of marine species behaviour, rooted in ancestral practices and passed down orally through generations.

Cleaning and Repairing Fishing Nets

In preparation for the Meci harvest, community members focus on cleaning and repairing their fishing nets to ensure they are effective and gentle on the delicate sea worms. Small-mesh nets are commonly used, as they allow for the careful collection of Meci without causing harm. These nets are thoroughly washed, inspected for holes, and carefully mended using traditional materials such as natural woven leaf fibbers or nylon thread. This process not only preserves the tools needed for harvesting but also highlights the community’s resourcefulness, environmental awareness, and respect for cultural practices.

7. LOCAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE (LEK) AND PRACTICES

7.1. Indigenous Ecological Understanding of Meci Life Cycle and Behaviour.

The indigenous ecological understanding of the Meci (Palola viridis) life cycle and behaviour in Lautem, Timor-Leste, is deeply rooted in traditional knowledge passed down through generations. Locals recognize that Meci are marine worms that emerge seasonally during specific lunar phases, which are closely observed and marked by ancestral rituals like the Attach the rope (Kesi Tali) . This timing aligns with natural cycles of the sea and moon, signalling the ideal moment for harvesting. The community understands Maci’s behaviour as a delicate and fleeting phenomenon, appearing only briefly at night when conditions are right. They view Meci not just as a resource but as a spiritual manifestation connected to the health of the ocean and the balance of the ecosystem. This awareness guides sustainable harvesting practices, ensuring that the worms are collected respectfully and only during sacred periods, allowing populations to regenerate and maintaining the harmony between humans, nature, and ancestral spirits.

7.2. Customary Law and Environmental Protection

In the indigenous communities of Timor-Leste, elders play a central role in establishing and enforcing customary laws, known as Tara Bandu. This traditional system serves as a form of community-based regulation that guides and governs behaviour, particularly in the context of natural resource management. During the Meci harvesting season, Tara Bandu is used to regulate participation, ensuring that all community members follow sustainable practices and avoid actions that could damage the marine ecosystem or disrupt traditional knowledge systems. More than just rules, Tara Bandu carries moral and cultural authority, teaching people the importance of conservation, protection, and preservation. It reinforces the community’s collective responsibility to respect the environment and pass on these values to future generations.

7.3. Traditional Harvesting Techniques.

Gathering and Announcement

Before the harvest begins, the community assembles at the shoreline. A designated leader guides participants to a ritual tree, where they receive ‘Blessing’ a customary blessing meant to safeguard them as they enter the sea.

Lighting the Fire

As the time to enter the sea draws near, the community prepares for one final sacred act. At the center of the beach, the elders have built a large communal fire, its flames crackling with purpose. Each participant carries their own of dried coconut’s leaf

The Harvest Begins

People use the torches and coconut dried leaf that lighting on the beach and step into the shallow water with People use the torches on the beach and step into the shallow water with small baskets hanging around their necks. They divide themselves into a few different groups and stand in a circle side by side and sing Fataluku song: ‘koinenepe’. The people believe that the use of the torches and singing the song will attract plenty of meci to the surface of shallow water. They then catch the meci with their hands and nets and put and pour them into their baskets.

Using Traditional Knowledge

In Lautem Municipality, the local community collects Meci (Palola viridis) using traditional ecological knowledge that has been passed down through generations. One of the most common methods involves harvesting the sea worms by hand, especially during their seasonal appearance along the coast. This method not only reflects the community’s deep understanding of the marine environment and natural cycles but also highlights their respect for ancestral practices. By relying on these customary techniques, the people of Lautem not only preserve their cultural heritage but also uphold the dignity of indigenous knowledge systems, reinforcing a strong connection between nature, tradition, and identity.

8. SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE

Role of Meci in Household income and Local Markets in Eastern Timor-Leste.

Palola viridis, commonly known as meci, is a seasonal marine worm that plays a significant role in the livelihoods of coastal communities in the eastern part of Timor-Leste. It appears predictably during specific lunar phases typically around March and April and this natural event is both highly anticipated and deeply rooted in local traditions.

During its seasonal emergence, meci becomes a valuable economic resource. In places like Lospalos, local families, especially those reliant on fishing, collect meci in large quantities to sell in the local markets. Traditionally, ancestors shared meci only within families and villages, promoting harmony and unity. However, since around 2018, during the modern era, communities began actively marketing it, recognizing its economic potential. Today, meci is sold at USD $5 per bottle of water in local markets, offering a significant source of household income for many families with limited year-round employment opportunities.

Consumption Patterns (Food Security, Medicinal Use, Etc.).

Sea worm (Palola viridis) or Meci in the context of Timor-Leste is not merely a seasonal source of protein, it plays a multifaceted role in the food systems, health practices, and spiritual lives of coastal communities in Lautem Municipality, particularly in Com, Lore I and Tutuala As a nutritious and readily available marine resource, it contributes directly to food security during its emergence season. Families often consume it fresh, cooked in traditional ways, while others preserve it for later use, ensuring continued nourishment even after the season ends.

Beyond its nutritional value, meci is also believed to possess medicinal and healing properties. It is used in traditional health practices, especially among elders who associate its consumption with restoring physical vitality and internal balance. Some also believe it strengthens the immune system and enhances overall well-being.

The spiritual and cultural significance of meci cannot be understated. As Francelino Fernandes Xavier, a respected elder from Com Village, explains:

“Meci Is Not Just Food For Us. It Is A Sacred Gift From The Ocean, A Symbol Of Our Ancestors’ Blessings. We Believe It Carries Healing Power, Both Physical And Spiritual.”

This statement reflects how deeply meci is woven into the community’s worldview. It is not only a source of nourishment but also a symbol of ancestral connection, oceanic harmony, and spiritual resilience. Its annual arrival marks a time of communal gathering, ceremonial sharing, and cultural reaffirmation.

In this context, meci serves as more than a resource, it is a living expression of identity, blending ecology, culture, and spirituality in the daily lives of the people of Timor-Leste’s eastern coast.

Gender Roles in Harvesting .

In the eastern part of Timor-Leste, particularly in municipalities such as Lautem, the harvesting of Meci (Palola viridis) is a unique cultural event that encourages equal participation from both men and women. This traditional practice stands out as an inclusive livelihood activity where gender roles are balanced, and everyone regardless of age or gender is welcomed to contribute.

During the Meci season, entire families gather along the shorelines at night, guided by tradition light and tide cycles. Women and men work side by side, collecting the worms using nets, buckets, and bottles. The communal nature of this practice strengthens social bonds, promotes gender cooperation, and ensures that economic benefits are shared across households.

Unlike many other traditional roles in rural economies that often assign labour by gender, Meci harvesting reflects a culturally rooted form of gender equity. Women are not only gatherers but also active participants in preparing, processing, and marketing the harvest. Their contributions are valued, and in some cases, women lead the trade in local markets, further reinforcing their role in the household economy.

This inclusive approach fosters not just shared income opportunities but also empowerment, as women gain visibility and decision-making roles within both families and communities.

9. RECENT CHANGES AND EMERGING CHALLENGES

Modernization Effects and Emerging Challenges in Lautém, Timor-Leste

In Lautém Municipality, the effects of modernization have brought significant cultural shifts, especially in relation to traditional practices such as the gathering of meci (Palola viridis), a seasonal sea worm with deep ceremonial and communal value. This loss is not merely about the replacement of traditional tools with modern ones, it represents a deeper erosion of identity. As traditional equipment is abandoned in favour of plastic containers, the practices lose their spiritual significance and cultural context. What was once a meaningful ritual risks becoming a routine task.

One of the most pressing challenges is the generational disconnect. Many young people are not learning the symbolic meanings and ancestral knowledge associated with meci gathering. In the past, this knowledge was passed down orally through stories, ritual instruction, and community involvement. Today, that transmission is being disrupted. Without structured efforts to preserve and share this heritage, such wisdom could vanish within a generation or two.

Compounding these cultural losses are environmental shifts. Traditionally, communities used the lunar cycle to predict the spawning of meci, ensuring its sustainable harvest. However, the younger generation often lacks this knowledge and struggles to observe or interpret the lunar patterns correctly. Climate change has further disrupted these natural indicators, making it harder to rely on traditional signs. Additionally, modern fishing tools and methods, while more efficient, can lead to overharvesting and threaten the ecological balance that sustained these practices for centuries.

Together, these challenges highlight the urgent need to preserve and revitalize traditional knowledge systems, not only to protect cultural identity but also to ensure ecological sustainability and community resilience in the face of rapid change.

10. SUSTAINABLE PERSPECTIVES AND COMMUNITY-BASED APPROACHES

Possibilities for Community-Led Conservation or Co-Management.

Empowering local communities to take ownership of resource conservation is vital. Establishing community-led marine resource committees or co-management agreements with local government can ensure that traditional users of Meci play a central role in regulating its harvest. These groups can enforce seasonal restrictions, designate no-take zones, and revive customary marine tenure practices. Strengthening village leadership and elder participation in decision-making fosters both compliance and cultural continuity.

Revitalization of Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

Reviving Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is key to restoring cultural identity and sustainable practices. This can be achieved by organizing intergenerational knowledge-sharing events, storytelling sessions, and cultural festivals focused on Meci. Elders can teach younger generations how to read the lunar cycle, interpret ocean signs, and practice respectful harvesting. Embedding TEK into local school curricula and community workshops can formalize its transmission and boost pride in cultural heritage.

Integration with Modern Scientific Approaches.

Rather than opposing modern science, communities can integrate traditional knowledge with scientific methods to enhance understanding and stewardship. For example, lunar-based TEK can be paired with marine biology research to predict Meci spawning with higher accuracy. NGOs and universities can support communities with data collection (e.g., water temperature, salinity) while respecting local customs and governance. This co-learning model enhances legitimacy and creates a shared language between elders, youth, and external experts.

Recommendations for Sustainable Harvesting and Knowledge Preservation.

- Seasonal Monitoring: Align harvesting periods with lunar phases and ecological indicators, supported by both local observation and scientific tracking.

- Cultural Education: Include Meci-related traditions, songs, and taboos in local school and youth programs.

- Documentation Projects: Support initiatives that record oral histories, rituals, and traditional methods through audio, video, or community books.

- Tool Use Regulations: Encourage the use of traditional harvesting tools where possible, and regulate modern equipment to prevent overharvesting.Incentivize Elders: Provide platforms and support for elders to mentor youth, possibly through small grants or recognition programs.

CONCLUSION

- Summary of findings.

This report has highlighted the profound cultural, environmental, and generational challenges facing the traditional harvesting of Meci (Palola viridis) in Lautém Municipality, Timor-Leste. Modernization has led to the widespread replacement of traditional tools, disrupting not only sustainable harvesting practices but also weakening the cultural identity tied to ancestral knowledge. Generational disconnect, climate-related unpredictability, and declining community transmission of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) further threaten this heritage.

- Reflection on the importance of integrating local knowledge in sustainability efforts

Local and traditional knowledge systems, particularly those rooted in lunar cycles, spiritual beliefs, and communal rituals, remain vital to both the cultural survival of Timorese communities and the ecological resilience of marine ecosystems. Integrating TEK with scientific frameworks can produce more holistic, culturally appropriate conservation strategies. Community-led governance, when supported by policy and resources, allows for sustainable practices that are grounded in lived experience and environmental stewardship.

- Future research directions or policy recommendations.

- Further research is needed to document the oral histories and ecological practices of elders before they are lost.

- Policy interventions should support co-management frameworks where local leaders, government agencies, and NGOs work collaboratively to regulate Meci

- Education reforms should integrate TEK into local school curricula to strengthen intergenerational knowledge transmission.

- Climate resilience strategies should consider both scientific data and community observation to maintain balance between sustainability and cultural tradition.

- Academic and local sources.

This report draws on a range of sources, including academic studies on marine biology and cultural heritage in Timor-Leste, as well as documentation from Fishery and Marine Science Department at UNTL , indigenous Community and conservation efforts led by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

- Oral testimonies

Insights have also been informed by oral testimonies from local elders and youth, collected through semi-structured interviews and participatory mapping sessions in Lautém villages. These voices provide first-hand accounts of changing practices, challenges, and hopes for cultural revitalization.

- Government or NGO reports.

Data and contextual understanding for this research were further supported by reports and collaborations from the following institutions and individuals:

- Fishery and Marine Science Department at the National University of Timor-Lorosa’e (UNTL), which provided foundational knowledge and access to local marine ecological data relevant to Meci harvesting and coastal resource use.

- IRD France (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement), whose ongoing research in Timor-Leste contributed valuable insights into marine ecological monitoring and the integration of traditional knowledge systems into coastal resource management.

- Ariadna Burges, who served as my research supervisor and provided essential academic guidance. Her expertise in marine resource use and cultural practices in Timor-Leste has significantly informed both this study and broader community-based conservation models across the country.

- REFERENCES

Academic and Local Sources

- Schulze, A. (2006). Phylogeny and genetic diversity of Palolo worms (Eunicidae, Polychaeta, Annelida). Biological Bulletin, 210(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134554

- Maleki Ratu. (2025). Interviews and participatory discussions with Fataluku community members in Lautém Municipality, Timor-Leste. Collected by Zeconio Fidel Dos Santos during field research.

- Amaral, A. (2018). Traditional Fishing Knowledge in Timor-Leste: Cultural Continuity and Challenges. Dili: Universidade Nacional Timor Lorosa’e (UNTL) Press.

- McWilliam, A. (2003). Timorese Seascapes: Marine Cosmologies in East Timor. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 4(2), 145–167.

- Palmer, L., & Carvalho, D. (2008). Nation Building and Resource Management in Timor-Leste. Environmental Management, 41(3), 361–373.